This post is associated with a GitHub repository.

TLDR; You’ve explored GitHub Actions for a while, and you’re now ready to create your own action and publish it to the marketplace. That’s brilliant, before you do that, let’s discuss adopting a simple design pattern that will make your creative journey much easier!

Folder structure of an action

A simple Node.js action would look like this:

./simple-action/

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── action.yml

├── dist

│ └── index.js

├── index.js

├── package-lock.json

└── package.json

index.js is where all the logic is encapsulated and action.yml is used to contain the action’s metadata as well as defining its interface (inputs and outputs).

A lot of actions on the marketplace adopt this very simple structure, and it’s great! However, not all actions are this simple.

With actions doing more complex things testability and maintainability become really difficult with this approach. Why?

-

Testing a change requires that you commit and push your changes upstream, then trigger a workflow run under the conditions your action is expecting. This is very time-consuming.

-

Updating the interface can become a challenge especially when you want to maintain backward compatibility.

You might say: hey! act is a wonderful project that allows you to run and test actions on your machine. Yes, but its only problem is that during the initial iterations you want to test fast and fail quickly. You might also want to write some unit (integration?) tests.

The command pattern

Command pattern to the rescue. In short, this is a behavioral design pattern that allows you to encapsulate all the information about the task in a single object which can then be invoked by certain triggers.

I’m definitely not going to do a better job at explaining this concept more than: https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/command

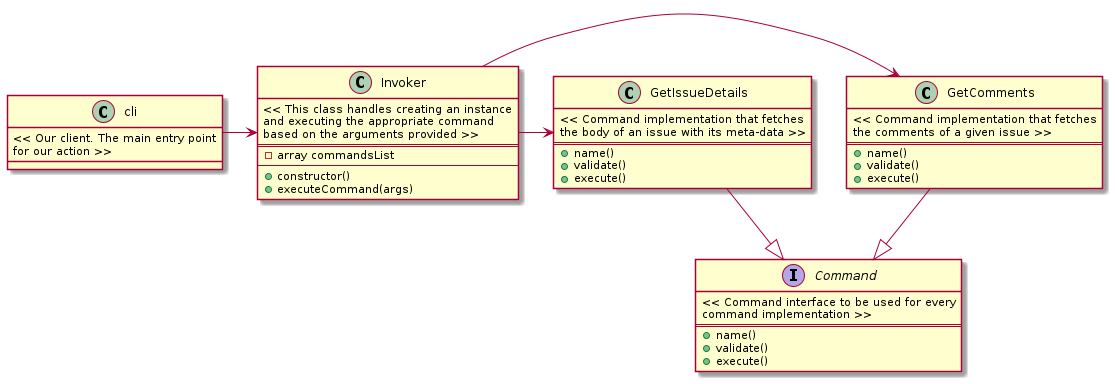

Unified command interface

There’s a better looking class diagram here: https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/command#pseudocode

What the class diagram above is trying to explain is:

cliwill create an instance ofInvokerInvokerwill load all the classes that implement theCommandinterfaceInvokerwill create instances ofGetCommentsandGetIssueDetailsclassesInvokerwill store the instances incommandsListcliwill then callexecuteCommand()and pass the arguments (inputs) it receivedInvokerwill callexecute()on the command matching the passed arguments fromcliand return the result from theCommandimplementation invoked

cli is never aware which commands are called. It doesn’t even need to be aware of inner workings of any command. cli will always have a single interface that it needs to be aware of.

The logic of instantiating and invoking commands is all encapsulated in 1 place, the Invoker object.

You can add an unlimited number of commands. As long as they implement the Command interface the Invoker will make sure they are loaded and instantiated to be used by any client.

Let’s implement this

simple-action/

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── action.yml

├── dist

│ └── index.js

├── package-lock.json

├── package.json

└── src

├── cli.js

├── commands

│ ├── getComments.js

│ ├── getIssueDetails.js

│ └── index.js

├── interfaces

│ └── command.js

└── invoker.js

Our folder structure should now look like 👆. Let’s look at the source code:

cli.js

const meta = require("../package.json");

const Invoker = require("./invoker");

const core = require("@actions/core");

const { Command } = require("commander");

const program = new Command();

/**

* We make use of the default option to fetch the input from our action

* with core.getInput() only when a value has not been supplied via the CLI.

* What this means is that, if you provide these parameters the values from

* the action will be ignored.

*

* This will guarantee that this tool will operate as an action but has an

* alternative trigger via the CLI.

*/

program

.version(meta.version)

.option(

"-c, --command <command name>",

"Command to execute",

core.getInput("command")

)

.option(

"-t, --token <token>",

"Personal Access Token or GITHUB_TOKEN",

core.getInput("token")

)

.option(

"-i, --issue-number <number>",

"Issue number",

core.getInput("issue-number")

)

.option("-o, --org <org_name>", "Organisation name", core.getInput("org"))

.option("-r, --repo <repo_name>", "Repository name", core.getInput("repo"))

.parse();

/**

* await won’t work in the top-level code so we have to wrap it with an

* anonymous async function and invoke it

*

* More details: https://javascript.info/async-await

*/

(async () => {

try {

const options = program.opts();

const invoker = new Invoker(options);

const result = await invoker.executeCommand(options);

core.setOutput("result", result);

} catch (Error) {

core.setFailed(` ⚠️ ${Error.message}`);

}

})();

invoker.js

const commands = require("./commands");

class Invoker {

constructor(options) {

this.commandsList = {};

this.options = options || null;

this.loadCommands();

}

/**

* Create a new instance of each command loaded from ./commands

* and add it to the commandsList instance variable

*/

loadCommands() {

commands.reduce((accumulator, command) => {

let instance = new command(this.options);

accumulator[instance.name()] = instance;

return accumulator;

}, this.commandsList);

}

/**

* Runs a number of checks and attemps to execute a command

* @param {Object} options

* @returns

*/

async executeCommand(options) {

// It's possible to supply an empty string as a command name so we have

// to guard against this

if (!options.command) {

throw new Error(

"required option '-c, --command <command name>' command name must be supplied"

);

}

// We need to make sure the command name provided matches the name of one of

// our loaded commands. Remember, loadCommands() uses the command name

// as the key in the commandsList dictionary

if (!(options.command in this.commandsList)) {

throw new Error(`${options.command} not found in the loaded commands`);

}

const command = this.commandsList[options.command];

// If all the checks pass, we're good to execute the command

return await command.execute(options);

}

}

module.exports = Invoker;

interfaces/command.js

/**

* This will behave as an abstract class for all the commands we're going to

* create that adopt this interface

*/

class Command {

constructor(options) {

if (this.constructor === Command) {

throw new Error("Abstract classes can't be instantiated.");

}

}

name() {

throw new Error("Method 'name()' must be implemented first");

}

validate() {

throw new Error("Method 'validate()' must be implemented first");

}

async execute() {

throw new Error("Method 'execute()' must be implemented first");

}

}

module.exports = Command;

commands/getComments.js

This is a sample command implementation

const Command = require("../interfaces/command");

class GetComments extends Command {

constructor() {

super();

}

name() {

return "get_comments";

}

/**

* Run all the validations necessary before you attempt to execute

* the command. Here we are doing a simple test just to illustrate the

* purpose of this method.

*

* @param {Object} options

* @returns validation result

*/

validate(options) {

if (Object.keys(options).length <= 2) {

throw new Error(`Command options must be provided`);

}

return true;

}

/**

* Attempts to execute the work

*

* @param {Object} options

* @returns Result of the execution

*/

async execute(options) {

this.validate(options);

return JSON.stringify({

status: "OK",

output: `${this.name()} executed successfully 🙌`,

});

}

}

module.exports = GetComments;

commands/getIssueDetails.js

This is another sample command implementation.

const Command = require("../interfaces/command");

class GetIssueDetails extends Command {

constructor() {

super();

}

name() {

return "get_issue_details";

}

/**

* Run all the validations necessary before you attempt to execute

* the command. Here we are doing a simple test just to illustrate the

* purpose of this method.

*

* @param {Object} options

* @returns validation result

*/

validate(options) {

if (Object.keys(options).length <= 2) {

throw new Error(`Command options must be provided`);

}

return true;

}

/**

* Attempts to execute the work

*

* @param {Object} options

* @returns Result of the execution

*/

async execute(options) {

this.validate(options);

return JSON.stringify({

status: "OK",

output: `${this.name()} executed successfully 🙌`,

});

}

}

module.exports = GetIssueDetails;

commands/index.js

This is a neat little trick that will allow us to import all the commands listed in it without looping through the content of the path and requiring each file individually. When require is given the path of a folder, it’ll look for an index.js file in that folder; if there is one, it uses that, and if there isn’t, it fails. To prevent this failure, we create an index.js and require all the individual commands.

module.exports = [require("./getComments"), require("./getIssueDetails")];

Easier tests, better extensibility

With the above you can easily implement tests per command as their logic is now decoupled from the workflow’s interface requirements. Adding more commands is simple as creating a new file and updating the required inputs (if necessary).

It’s definitely more boilerplate code but if you’re building complex workflows, this is definitely the way to go.

If you do implement this approach, reach out to me via Twitter I’d love to read your thoughts on it!